The Holy Spirit: The Feminine Aspect Of the Godhead

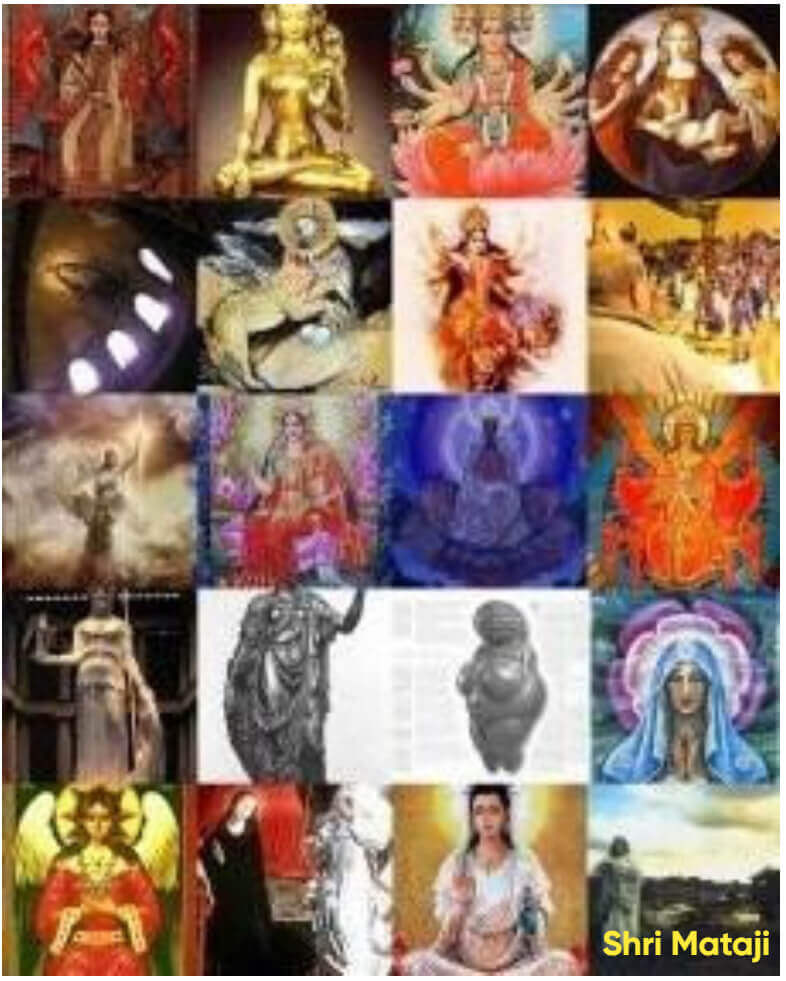

This article explores the feminine identity of the Holy Spirit through ancient texts, Gnostic scriptures, and early Christian mysticism. Drawing from the Dead Sea Scrolls, Nag Hammadi, and intertestamental writings, it reveals how the Holy Spirit—Ruach Ha Kodesh, Shekinah, and Pneuma—was originally understood as the feminine presence of God. The Eastern Church, Coptic-Gnostics, and early mystics revered Her as the indwelling Comforter, the Mother of Jesus, and the creative force of divine wisdom. This revelation, long suppressed by patriarchal theology, is now reemerging through spiritual and scholarly insight. Shri Mataji’s incarnation as the Adi Shakti fulfills this ancient truth, restoring the Holy Spirit to Her rightful place as the Divine Mother within.

The feminine aspect of the Holy Spirit has found renewed recognition in both contemporary scholarship and mystical theology, particularly through the teachings and ministry of the Paraclete Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi. Drawing from ancient Christian, Jewish, and wider religious traditions, the identification of the Holy Spirit as the Divine Feminine—embodied most fully in Shri Mataji's life and message—offers a significant correction to patriarchal interpretations that have long shaped mainstream doctrine.[1][2][3]

Introduction

The debate over the gender and role of the Holy Spirit is not simply a linguistic or theological curiosity—it is central to the question of how the Divine relates to and manifests within creation. J. J. Hurtak's analysis, supported by discoveries from the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi library, suggests that the early church understood and honored the feminine presence of the Holy Spirit—referred to as Ruach in Hebrew (a feminine noun), and Shekinah in Aramaic, both signifying the indwelling, nurturing power of God.[2][3][4]

Linguistic and Scriptural Foundations

- In Hebrew and Aramaic, the terms "Ruach" and "Shekinah" for Spirit are feminine, indicating the early conception of the Spirit as a maternal presence.[3][1]

- Early Syriac Christianity also described the Holy Spirit explicitly as the Mother, with church fathers like Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and Jerome referencing the feminine principle inherent in Spirit.[5][1]

- Gnostic texts such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Secret Book of John, and the Acts of Thomas feature the Holy Spirit in the role of a divine Mother, partner of the Father, and source of wisdom and life.[2]

Historical Marginalization and Suppression

Patristic writers such as Augustine worked to suppress the feminine interpretation of the Spirit, branding it as "pagan" or heretical. However, evidence from early Christian art, as well as liturgical and non-canonical literature, indicates that many Christian communities retained a living awareness of the Holy Spirit as the Divine Mother well into the Middle Ages.[3][2]

The Paraclete Shri Mataji and Restoration of the Divine Feminine

- Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, through the teachings of Sahaja Yoga and her personal testimony, positions herself as the Paraclete (Comforter) promised by Christ—an embodiment of the Holy Spirit who comes to guide, heal, and nurture humanity in the eschatological "Age to Come".[6][1]

- Her identification with the Adi Shakti, the primordial creative force of the universe in Hinduism, bridges Christian and Eastern mystical traditions, revealing the universality of the Divine Feminine as the source of spiritual rebirth, wisdom, and inner ascent.[7][8][1]

- This restoration not only affirms the feminine side of divinity but also invites a renewed spiritual balance—one that honors both the Father and the Mother, challenging the historical overemphasis on masculine imagery in Western theology.[1]

Impact on Contemporary Spiritual Dialogue

Reclaiming the Holy Spirit as the feminine energy or Divine Mother does more than correct theological distortions; it has profound psychological and societal implications. Recognizing the Holy Spirit's maternal, indwelling, and nurturing role can open believers to deeper experiences of spiritual guidance, unconditional love, and creative transformation.[4][5][3]

This view also takes on ecumenical significance, integrating perspectives from Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism. The presence of feminine divinity contextualizes the "Age of the Spirit" as something deeply inclusive, compassionate, and transformative—fulfilling Hurtak's vision of a future "crowned with feminine design."

Conclusion

The feminine aspect of the Godhead, manifest in the Holy Spirit and embodied in the Paraclete Shri Mataji, reclaims ancient truths for modern seekers and theologians. When integrated into the practice of faith, this restored vision opens the possibility for a creative and harmonious future, inviting all to experience the Divine not as an abstract patriarch but as a loving Mother, Source, and Guide.[1][2][3]

The significance of this restoration, as illuminated by Shri Mataji and confirmed by new spiritual and scholarly discoveries, is nothing less than a profound reshaping of both spiritual consciousness and communal life, calling believers to recognize and honor the full breadth of the Divine Mystery.

Key Sources

- [1] Adi Shakti.org - Holy Spirit of Christ is a Feminine Spirit

- [2] Adi Shakti.org - Holy Spirit: The Feminine Aspect of the Godhead

- [3] Adi Shakti.org - Feminine Gender of the Holy Spirit

- [4] HTS Theological Studies - Article on Holy Spirit

- [5] Deidre Havrelock - The Holy Spirit as Feminine

- [6] Adi Shakti.org - The Paraclete

- [7] Sikh Dharma - Adi Shakti

- [8] Tara Krishan - Understanding Feminine Energy

The Holy Spirit: The Feminine Aspect Of the Godhead

J. J. Hurtak, PhD, The Academy For Future Science

A new response to the "image" of the Holy Spirit is taking shape quietly in scholarly circles throughout the world, as the result of new findings in the Dead Sea Scriptures, the Coptic Nag Hammadi and intertestamental texts of Jewish mystics found side-by-side the writings of the early Christian church. Scholars are recognizing the Holy Spirit as the "female vehicle" for the outpouring of higher teaching and spiritual rebirth. The Holy Spirit plays varied roles in Judeo-Christian traditions: acting in Creation, imparting wisdom, and inspiring Old Testament prophets. In the New Testament She is the presence of God in the world and a power in the birth and life of Jesus.

The Holy Spirit became well-established as part of a circumincession, a partner in the Trinity with the Father and Son after doctrinal controversies of the late 4th century AD solidified the position of the Western Church. Although all Christian Churches accept the union of three persons in one Godhead, the Eastern Church, particularly the communities of the Greek, Ethiopian, Armenian, and Russian, do not solidify a strong union of personalities, but see the figures uniquely differentiated, but still in union. Moreover, the Eastern Church places the Holy Spirit as the Second Person of the Trinity with Christ as the Third, whereas the Western Church places the Son before the Holy Spirit. In the Old Testament and the Dead Sea Scrolls the Holy Spirit was known as the Ruach or Ruach Ha Kodesh (Psalm 51:11). In the New Testament as Pneuma (Romans 8:9). The Holy Spirit was not rendered as "Holy Ghost" until the appearance of the 1611 Protestant King James Version of the Bible. For the most part, Ruach or Pneuma have been considered the spiritual force or presence of God. The power of this force can be seen in the Christian church as the "gifts of the Spirit" (especially in today's tongues- speaking Pentecostals). The Holy Spirit was also a source for Divine guidance and as the indwelling Comforter.

Likewise in Hebrew thought, Ruach Ha Kodesh was considered a voice sent from on high to speak to the Prophet. Thus, in the Old Testament language of the prophets, She is the Divine Spirit of indwelling sanctification and creativity and is considered as having a feminine power. "He" as a reference to Spirit has been used in theology to match the pronoun for God, yet the Hebrew word ruach is a noun of feminine gender. Thus, referring to the Holy Spirit as "she" has some linguistic justification. Denoting Spirit as a feminine principle, the creative principle of life, makes sense when considering the Trinity aspect where Father plus Spirit leads to the Divine Extension of Divine Sonship.

The Spirit is not called "it" despite the fact that pneuma in Greek is a neuter noun. Church doctrine regards the Holy Spirit as a person, not a force like magnetism. The writings of the Catholic fathers, in fact, preserve the vision of the Spirit encapsulating the "peoplehood of Christ" as the Bride or as the "Mother Church.” Both are feminine aspects of the Divine. In the Eastern Church, Spirit was always considered to have a feminine nature. She was the life -bearer of the faith. Clement of Alexandria states that "she" is an indwelling Bride. Amongst the Eastern Church communities there is none more clear about the feminine aspect of the Holy Spirit as the corpus of the Coptic-Gnostics. One such document records that Jesus says, "Even so did my mother, the Holy Spirit, take me by one of my hairs and carry me away to the great mountain Tabor [in Galilee].”

The 3rd century scroll of mystical Coptic Christianity, The Acts of Thomas, gives a graphic account of the Apostle Thomas' travels to India, and contains prayers invoking the Holy Spirit as "the Mother of all creation" and "compassionate mother," among other titles. The most profound Coptic Christian writings definitely link the "spirit of Spirit" manifested by Christ to all believers as the "Spirit of the Divine Mother.” Most significant are the new manuscript discoveries of recent decades which have demonstrated that more early Christians than previously thought regarded the Holy Spirit as the Mother of Jesus.

One text is the Gospel of Thomas which is part of the newly discovered Nag Hammadi texts (discovered 1945-1947). Most are composed about the same time as the Biblical gospels in the 1st and 2nd century AD. In this gospel, Jesus declares that his disciples must hate their earthly parents (as in Luke 14:26) but love the Father and Mother as he does, "for my mother (gave me falsehood), but (my) true Mother gave me life.” In another Nag Hammadi discovery, The Secret Book of James, Jesus refers to himself as "the son of the Holy Spirit.” These two sayings do not identify the Holy Spirit as the mothering vehicle of Jesus, but more than one scholar has interpreted them to mean that the maternal Holy Spirit is intended.

So far in Western traditional theology, the voices advocating a feminine Holy Spirit are scattered and subtle. But for them, it is a view theologically defensible and accompanied by psychological, sociological, and scientific benefits of recognizing "the new supernature" developing within vast consciousness changes happening in the human evolution.

The German theologian Jürgen Moltmann, a well-known thinker in mainline Protestantism, says "monotheism is monarchism.” He says a traditional idea of God's absolute power "generally provides the justification for earthly domination"- - -from the emperors and despots of history to 20th century dictators. Moltmann argues for a new appreciation of the "persons" of the Trinity and the community or family model it presents for human relations.

According to Professor Neil Q. Hamilton at Drew University School of Theology, the Gospel of John shows us how "the Holy Spirit begins to perform a mothering role for us that is unconditional acceptance, love and caring.” God then begins to parent us in father and mother modes.

A Catholic scholar, Franz Mayr, a philosophy professor at the University of Portland, also favors the recognition of the Holy Spirit as feminine. He contends that the traditional unity of God would not have to be watered down in order for scholars to accept the feminine side of God . Mayr, who studied under the renown German theologian Karl Rahner, said he came to his view during his study of the writings of St. Augustine (AD 354-430) who saw that a significant number of early Christians must have accepted a feminine aspect of the Holy Spirit such that the influential church father of North Africa castigated this view. St. Augustine claimed that the acceptance of the Holy Spirit as the "mother of the Son of God and wife-consort of the Father" was merely a pagan outlook. But Mayr contends that Augustine "skipped over the social and maternal aspect of God," which Mayr thinks is best seen in the Holy Spirit, the Divine Ruach Ha Kodesh. St. Jerome, a contemporary of Augustine's, and two church fathers of an earlier period, Clement of Alexandria and Origen, quoted from the pseudopigraphic Gospel of the Hebrews, which depicted the Holy Spirit as a "mother figure.”

A 14th Century fresco in a small Catholic Church southeast of Munich, Germany depicts a female Spirit as part of the Holy Trinity, according to Leonard Swidler of Temple University. The woman and two bearded figures flanking her appear to be wrapped in a single cloak and joined in their lower halves showing a union of old and new bodies of birth and rebirth.

In conclusion, we are living at a time of profound and revelatory discoveries of archaeology and ancient spiritual texts that point the way to the future. Christ, himself, was said to have female disciples as disclosed in Gnostic literature and recent archeological findings of early Christian tombs in Italy. A beginning has been made to reclaim "the Spirit" of the Ruach found in the mountain of newly discovered pre-Christian texts and Coptic-Egyptian texts of the early Church . It is becoming clear in re-examining the first 100 years of Christianity that an earlier Christianity was closer to the "Feminine Spirit" of the Old Testament, the Ruach or the beloved Shekinah. The Shekinah, distinct from the Ruach, was seen as the indwelling Divine Presence that activated the "birth of miracles" or the anointed self. Accordingly, the growth of traditional Christianity made alternative adjustments of the original position of the "birth of gifts" as Christendom compromised for the privilege of becoming an establishment.

The new directions of spiritual and scientific studies are showing that it is now possible that the Holy Spirit, Ruach Ha Kodesh, can be portrayed as feminine as the indwelling presence of God, the Shekinah, nurturing and bringing to birth souls for the kingdom. Spiritual insights recorded in the Book of Knowledge: Keys of Enoch carefully remind us that we are being prepared to understand that just as the Old Testament was the Age of the Father, the New Testament the Age of the Son, so this coming Age where gifts are poured forth will be the Age of the Holy Spirit. However, the Keys also tell us that the Divine Trinity is beyond the anthropo-morphic forms of male and female. Here our own masculine or feminine natures are only symbols of the Divine and our Life's manifestation in the Universe. And herein we understand who we really are, as we both male and female make our own preparation for the rebirth of our "Christed Overself," unified as the peoplehood of Light, the "Bride," for the coming of the "Bridegroom"- - the Christ.”

J. J. Hurtak, PhD, The Academy For Future Science

The Truth at the Heart of the DVC

Elaine Pagels

"So many Christians throughout the world knew and revered these books that it took more than 200 years for hardworking church leaders who denounced the texts to successfully suppress them. [...]

Irenaeus said there could be only four gospels because, according to the science of the time, there were four principal winds and four pillars that hold up the sky. Why these four gospels? He explained that only they were actually written by eyewitnesses of the events they describe—Jesus' disciples Matthew and John, or by Luke and Mark, who were disciples of the disciples.

Few scholars today would agree with Irenaeus. We cannot verify who actually wrote any of these accounts, and many scholars agree that the disciples themselves are not likely to be their authors. [...]

What, then, do these texts say, and why did certain leaders find them so threatening?

First, they suggest that the way to God can be found by anyone who seeks. According to the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus suggests that when we come to know ourselves at the deepest level, we come to know God: "If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you.” This message—to seek for oneself—was not one that bishops like Irenaeus appreciated: Instead, he insisted, one must come to God through the church, "outside of which," he said, "there is no salvation.”

Second, in texts that the bishops called "heresy", Jesus appears as human, yet one through whom the light of God now shines. So, according to the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus said, "I am the light that is before all things; I am all things; all things come forth from me; all things return to me. Split a piece of wood, and I am there; lift up a rock, and you will find me there.” To Irenaeus, the thought of the divine energy manifested through all creation, even rocks and logs, sounded dangerously like pantheism. People might end up thinking that they could be like Jesus themselves and, in fact, the Gospel of Philip says, "Do not seek to become a Christian, but a Christ.”[...]

Worst of all, perhaps, was that many of these secret texts speak of God not only in masculine images, but also in feminine images. The Secret Book of John tells how the disciple John, grieving after Jesus was crucified, suddenly saw a vision of a brilliant light, from which he heard Jesus' voice speaking to him: "John, John, why do you weep? Don't you recognize who I am? I am the Father; I am The Mother; and I am the Son.” After a moment of shock, John realizes that the divine Trinity includes not only Father and Son but also the divine Mother, which John sees as the Holy Spirit, the feminine manifestation of the divine.”

Elaine Pagels

Perspective